Short-haul flights in Spain: is high-speed rail an alternative?

France has received the go-ahead from the European Commission to ban short-haul flights in trips for which there is a good rail alternative. In this article we review the fine print of the French law, identify which connections in Spain meet the criteria — or will do so with the planned infrastructures —, and analyse the effects that this may have for the passengers of some of the connections that are could be affected by this measure in Spain.

The aviation sector accounts for 2-3% of CO2 emissions globally and 4% of CO2 emissions in Europe, according to the “Fly the Green Deal” report, prepared by the European Commission in 2022. Climate change mitigation strategies include measures to reduce emissions from air transport, either by increasing the efficiency of flights or by promoting modal shift to cleaner options where possible. The growth of high-speed rail networks in Europe has raised the possibility of limiting short-haul flights in the continent by offering a competitive alternative in terms of door-to-door travel times. France has been the first country to legislate in this regard, banning some air connections where the rail alternative is fast enough. Although the measure was approved in 2021, it was not until December 2022 that it received the go-ahead from the European Commission. This debate has already spilled over into Spain, where the government’s official long-term strategy document “Spain 2050” recommends applying the French ban (page 196).

In this article we analyse which air connections in Spain are likely to meet the criteria of the French law and what effects this may have on passengers on the targeted connections.

The criteria of the French law: not just “2.5 hours”

The headline that has sunk in about the French measure is that it bans flights for which there is a rail alternative lasting less than 2.5 hours. However, it is worth reviewing in detail the applicable criteria before drawing conclusions about Spain: in addition to the travel time threshold, the French law provides for other criteria to be assessed for each connection between airports:

- The rail connection must be direct, without transfers between the cities where the airports are located.

- The rail connection must have “sufficient frequencies” as well as “satisfactory timetables“, so that more than 8 hours can be spent at both ends with a round trip within the day.

- If the busier of the two airports has a high-speed rail station, the travel time threshold applies to the connection between that station and the city station served by the other airport.

Initially, there were eight air links in France likely to be affected by the measure: the routes between Paris Charles de Gaulle and Bordeaux, Lyon, Rennes and Nantes; between Paris Orly and Bordeaux, Lyon and Nantes; and between Lyon and Marseille. However, the additional conditions have limited their application to only 3 routes. Paris Charles de Gaulle has a high-speed railway station and connections between this station and the stations of Bordeaux and Nantes take more than 2.5 hours. The connections between Paris Charles de Gaulle and the cities of Lyon and Rennes do not have train schedules that allow arriving early enough or leaving late enough to or from Paris Charles de Gaulle. The same applies to the link between Lyon airport and Marseille. Therefore, the only air connections that will be prohibited are those between Paris Orly and Bordeaux, Lyon and Nantes. The three cities will maintain their connection to the other major Parisian airport, Charles de Gaulle.

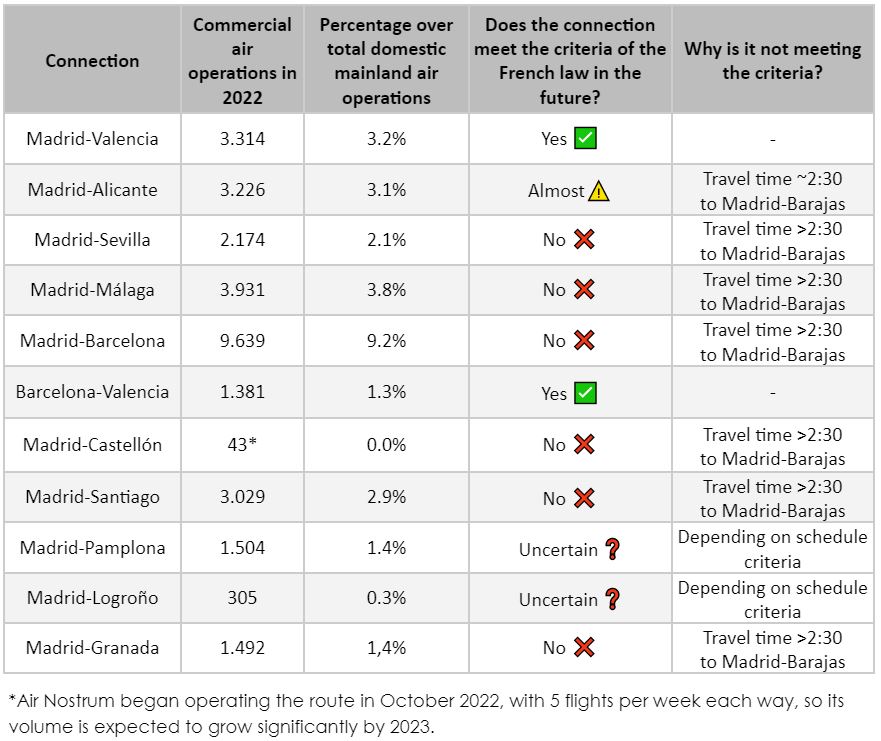

Application of the French law in Spain: a measure with limited impact

Spain is one of the countries in the world with the most developed high-speed rail network. This would position the country as one of the best prepared for the replacement of short-haul flights by high-speed rail connections. However, the analysis of mainland air connections and their alternatives by rail shows that the criteria of the French law are clearly met only in 4 connections (Madrid with Valencia, Alicante, Seville and Malaga). According to Aena data, these connections accounted for just over 12% of mainland commercial air operations in 2022. In all four cases, journey times are less than 2.5 hours, the timetables offered by the different rail operators allow travellers to spend 8 hours at the destination, and high frequencies are available (more than 10 daily services in each direction). The Madrid-Barcelona connection, responsible for 9.2% of mainland air operations in 2022, is right at the maximum travel time threshold: direct high-speed rail services offered by Renfe, Ouigo and Iryo take 2.5 hours to complete the journey between the two cities. What would happen if the travel time threshold were more flexible? 7.5% of mainland air operations in 2022 are associated with rail connections lasting between 2.5 and 3.5 hours. These are the connections between Madrid and the cities of Castellón, Santiago de Compostela, Pamplona, Logroño and Granada, as well as the Barcelona-Valencia connection. Some of these links have pending improvements to the railway infrastructure that could shorten journey times, so they should be taken into account in the future, although at present they are still above the minimum journey time threshold. Table 1 shows a summary of the air connections that could be replaced by high-speed rail services at present, based on the criteria of the French law, and their weight in the total mainland domestic air operations.

The analysis of what may happen in the future (once the high-speed network integrates the infrastructures already under construction or planned) reflects a paradoxical situation: the number of connections meeting the criteria of the French law could be reduced in the coming years, given the planned configuration of the Madrid-Barajas airport connection to the high-speed network. In the short and medium term, it is foreseen that the link will use the current double-track mixed-gauge tunnel used by the Cercanías service to reach the T4 station. With Barajas becoming the reference station for calculating journey times, only the connection to Valencia would still clearly meet the 2.5 hour criterion. Despite the benefits of the direct connection (e.g., reducing the number of transfers for passengers laden with luggage), there would be no further bans on short-haul flights.

On the one hand, services arriving at Chamartín from the south would take an additional 10-15 minutes to reach the airport. Although there is sufficient margin on the connection to Valencia, it is not possible to guarantee that the connection between Barajas and Alicante could fall below the 2.5 hour journey time. The same applies to services to Logroño and Pamplona, which use the Madrid-Zaragoza-Barcelona high-speed line and enter Chamartín from the south: it is not clear whether they meet this travel time threshold or have sufficient frequencies to consider eliminating the air link. On the other hand, the connection would not allow direct movements between the north high-speed line and the branch line to the airport, requiring a turn-back operation in Chamartín. This makes it very difficult to meet the threshold for the Madrid-Santiago link in the future, which could be around 2.5 hours if Chamartín were taken as reference. Although there is a consensus on the need for this way of accessing the airport to be transitory, a definitive plan on how to connect Barajas to the high-speed network in the long term has not been approved yet. In this scenario, the only new connection that would meet the criteria is Barcelona-Valencia, as its journey time would be reduced to less than 2.5 hours thanks to new actions such as the Valencia-Castellón high-speed line. This connection would continue to be based on the travel time between Valencia Joaquín Sorolla and Barcelona Sants, given that there are no plans to connect El Prat directly to the high-speed network. Table 2 shows a synthesis of how the connections analysed would or would not meet the criteria of the French law with the planned investments in the high-speed rail network.

What would this mean for connections with international flights?

Air connections between Madrid and other mainland airports serve a dual function: to allow fast travel between peripheral regions of the Iberian Peninsula and Madrid, and to feed long-haul flights using Madrid as a hub. The existing high-speed rail connections on the four routes which currently meet the criteria of the French law are sufficiently competitive to provide a good service to the traveller who wants to travel back and forth between Madrid and Valencia, Alicante, Seville or Malaga within the day. However, the question of connections with international flights in Madrid is more complex (as mentioned above, connections to Paris Charles de Gaulle airport were discarded for various reasons and exceptions included in the French law, so this problem is not relevant in the case of France).

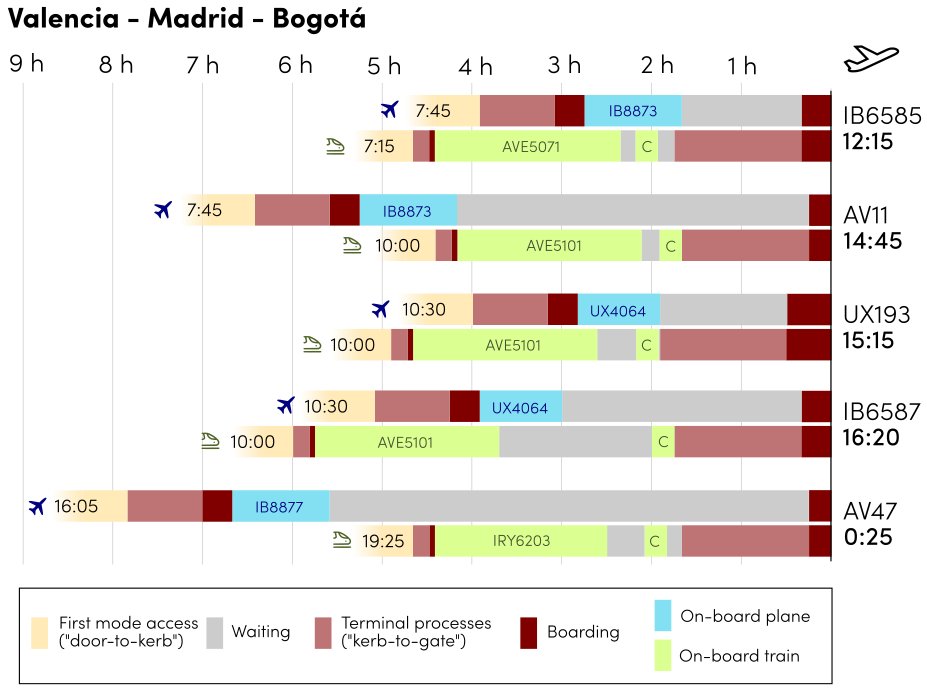

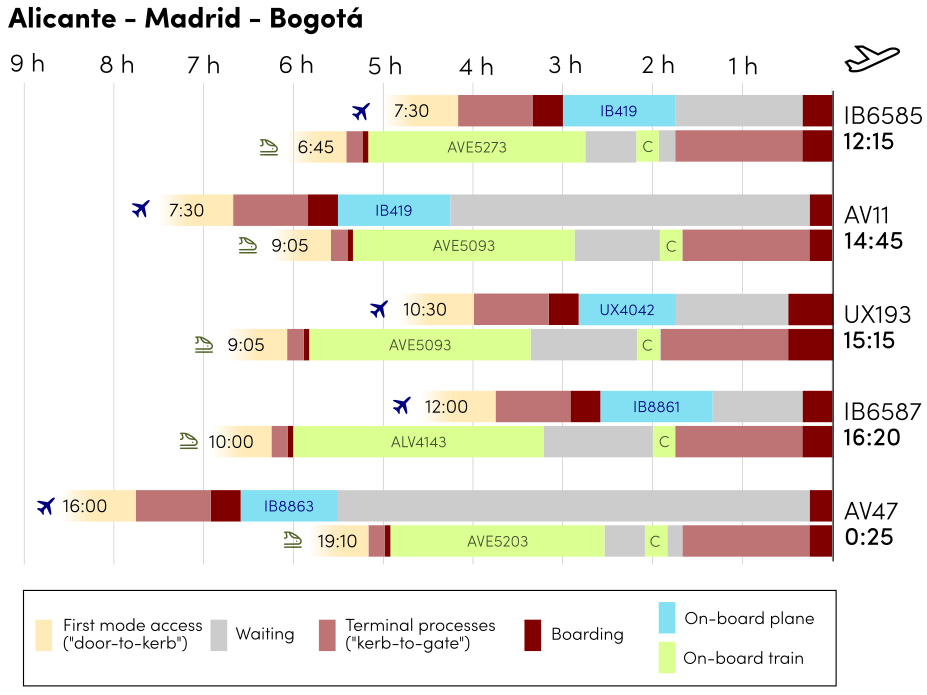

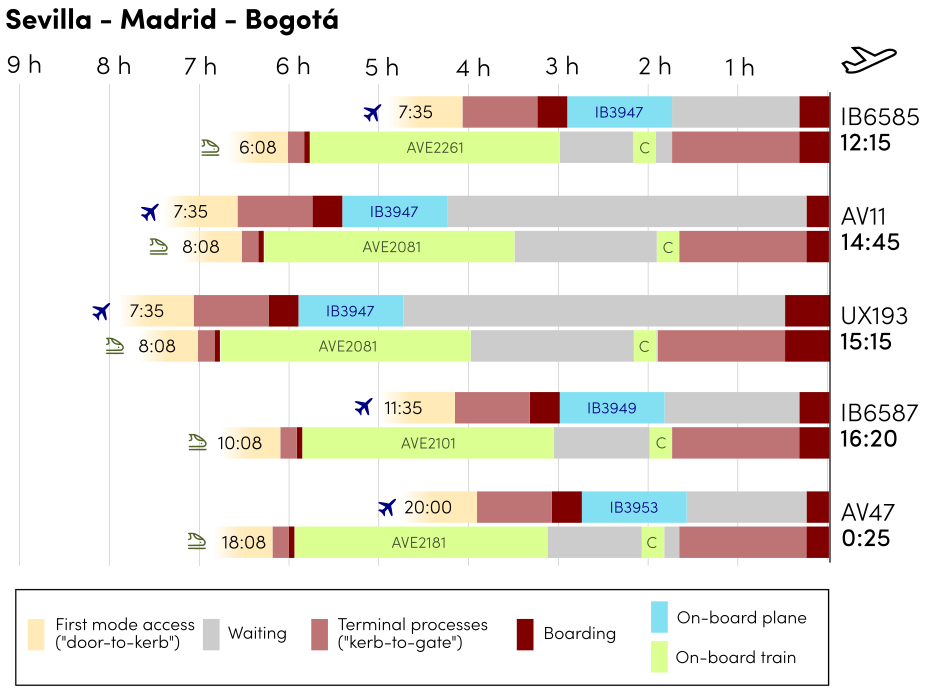

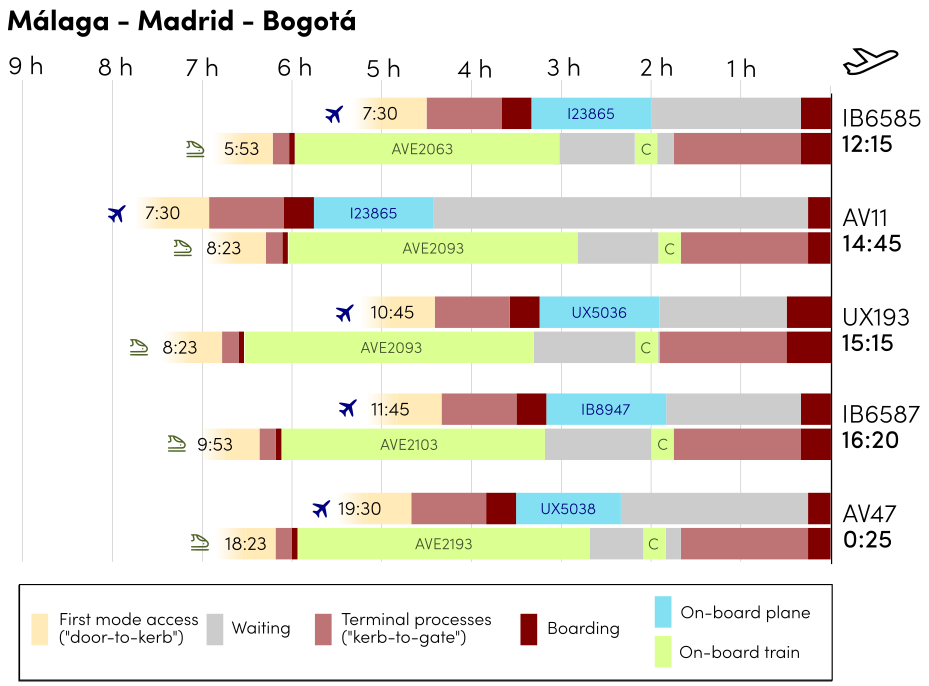

To illustrate the passenger effects of this measure, an analysis has been carried out on the alternatives for accessing Madrid airport from Valencia, Alicante, Seville and Malaga to take flights to Bogotá, the Latin American destination with the highest volume of passengers from Madrid in 2022. Taking as a reference the working days of March 2023, six daily connections to Bogotá are scheduled, five of which have a sufficiently late departure time to allow connecting access from other Spanish airports.

The following figures show how early a passenger needs to depart from these cities in order to board at the scheduled time in Madrid, whether they opt for a connecting flight from the corresponding airport or use the high-speed rail services. The diagrams are based on a number of assumptions:

- The average access time to railway stations is 20 minutes, while the average time to the airport is 35 minutes.

- For short-haul flights passengers arrive at the airport 40 minutes before the boarding time , which is between 20 and 30 minutes before the flight departure time. In the case of rail, these times are reduced to 15 and 5 minutes respectively.

- Passengers opting for a rail connection must be at the terminal at Barajas at least one hour and fifteen minutes before the boarding time of the intercontinental flight, in order to proceed to check-in and passport and security controls.

- High-speed services from Seville and Malaga are extended to Chamartin, with a journey time 15 minutes longer than the current one from Atocha (10-12 minutes between Atocha and Chamartin and 3-5 minutes stop at the Atocha transfer station). If services to/from Andalusia continued to start/end at Atocha, an increase of around 20 minutes in total journey time would be expected compared to that predicted in this analysis.

- Passengers who opt for the rail connection use the Cercanías services between Chamartín and Aeropuerto T4 to complete their access leg to Barajas.

The first conclusion of the analysis is that the impact depends on the supply of air connections available from the airlines operating between Madrid Barajas and Bogotá. Given the synchronisation of schedules between mainland and intercontinental flights by airlines using Madrid-Barajas as their hub, the rail option adds between 30 minutes and 2.5 hours of total travel time for passengers on Iberia and Air Europa flights. Logically, the difference is greater for connections with longer travel time by train (e.g., Seville), and less in the case of Valencia. While the increase in travel time is an inconvenience in itself, there are reasons to believe that its actual impact on the majority of passengers would be small. Firstly, the difference hardly ever means that there is no longer time for activities at the origin of the trip before starting the journey (e.g., meetings or visits), since in very few cases it is possible to leave the origin later than 10-11 a.m. if one opts for the plane (the train implies leaving at 8-9 a.m.). Secondly, the train allows work activities to be carried out more easily than the plane (internet connection, more space for electronic devices, etc.), so the time on board the train is likely to be more useful than time on board the plane, especially for business passengers. Thirdly, this is a small relative increase over the total intercontinental travel time (over 12 hours).

In contrast to Iberia and Air Europa, the train tends to offer shorter door-to-door journey times for connections of airlines which do not have their own connecting flights to other mainland destinations. This is observed for flights of the Colombian airline Avianca, with very few exceptions (e.g., the afternoon flight for passengers coming from Seville). In some cases, the favourable differences for the train exceed 3 hours, as in the case of the afternoon flight for passengers coming from Valencia or Alicante. If they opt for the plane, they must leave their origin at 4 p.m.; if they opt for the train, they can wait until 7 or 7.30 pm. The fact that these differences occur in the middle of the day means that some activities at the origin can be extended if it is convenient for the passenger (e.g., a meal, whether for business or leisure).

Is there room for improvement for the train to be even more competitive on these connections, so that it can achieve travel times similar to those of flights of airlines with a hub at Barajas? As mentioned above, the infrastructure planned to connect Barajas to the high speed network in the short and medium term will not imply a shorter on-board travel time: it approximately adds 15 minutes to the journey to Chamartín from the four cities (although, on the other hand, it has the benefit of the reduction in the number of transfers, which is especially attractive for users carrying heavy luggage). While it is true that this connection still opens up opportunities for greater synchronisation of timetables if services from Chamartín to Barajas are extended, the scope for reducing the differences between the travel times of the air and rail connections through greater air-rail synchronisation is limited by the time in advance with which passengers must present themselves at Barajas in order to check in their luggage and pass through security and passport controls. Only integration measures between airlines and rail operators could further reduce this gap (e.g., integrated baggage check-in).

The demand side perspective: the TRANSIT project

The increasing availability of geolocation data opens up new possibilities for assessing the consequences of decisions such as the one discussed in this article, as it provides valuable information about travel demand behaviour. With the aim of exploring these possibilities, Nommon has led the TRANSIT project, developed between 2020 and 2022 together with four partners (ENAC, ETH Zurich, Aena, and EUROCONTROL), and funded by the SESAR programme.

TRANSIT brings together recent advances in mobility data analysis and long-haul multimodal travel modelling to provide a methodological framework and a set of software tools to support the design, implementation and evaluation of new intermodal concepts and solutions based on a better integration of the European air transport system with land transport modes. One of the use cases explored by TRANSIT has been the analysis of the benefits of timetable synchronisation between rail and air transport, taking as a case study the Madrid-Barajas airport. The project’s White Paper Lessons learnt from the TRANSIT project and way forward provides a synthesis of this case study.

Conclusion

Spain’s extensive high-speed rail network suggests that France’s decision to ban certain short-haul flights in favour of rail use may be transferable to Spain. France prohibits air connections with a rail alternative with a travel time of less than 2.5 hours, with sufficient frequencies and extensive timetables to allow the traveller to spend at least 8 hours at both ends and return in the day. This is clearly the case on four routes in Spain today: those linking Madrid with Valencia, Alicante, Seville and Malaga. However, it must be taken into account that the French law stipulates that the travel time criteria must be applied on rail connections from the high-speed station integrated in the main airport of the connection, whenever it exists. The connection of the high-speed train with the Madrid-Barajas airport, planned for the coming years, will have a paradoxical effect if these criteria are taken into account: by increasing the travel time from some origins compared to the current time to Madrid’s Chamartín or Atocha stations, the number of connections included in the criteria would be reduced.

Regardless of how the French criteria are transposed to Spain, the analysis of the effect of this measure on passengers connecting at Barajas with intercontinental flights provides interesting insights for discussion. On the one hand, it is likely that the door-to-door journey time for a large proportion of such journeys would increase if flights between Madrid and the cities of Valencia, Alicante, Seville and Malaga were banned. On the other hand, this growth is mostly concentrated on passengers on flights that currently have more or less synchronised air connections from their origins, with the opposite effect for passengers of airlines without peninsular connections. Additionally, the increase in travel time is not very high compared to the total travel time and its impact would be relatively low for many passengers, as it does not impede activities that can now be carried out thanks to the speed of air connections and brings greater convenience for business passengers.

The advances in the analysis and modelling of long-haul travel demand and of multimodal solutions, driven by projects such as TRANSIT, will make it possible to anticipate the effects of such measures on the passenger experience and the sustainability of air transport.